Palavra Aleatorie (Random Word):

pulmonare - Definición en Inglech (English Definition): pulmonary: of the lungs | Tipo de Palavra (Type): adjective | Etimologíê (Etymology):

Learn how this started and why.

The Story & Purpose of Voç Comune

Voç Comune is an a posteriori language that is a combination of artistic 'conlang' and auxiliary language. It has over 13 thousand words and a well-developed grammar.

Most of the inspiration is from Romance languages as well as trade languages used as lingua francas. The pronunciation and word choices are largely influenced by Spanish and Portuguese as spoken in the Americas. While Spanish and Portuguese contribute the most to the language, there are some influences from Catalan, Occitan, Galician, Franco-Provençal, and Romansch. Papiamentu and other creole languages even contribute some.

My vision is and was to bring people together with

this mutually intelligible language. This site will discuss the language and compare it with features of other languages.

Search the Dictionary Database!

Right now, there are 14,113 entries in the dictionary!

Type in 3 or more letters to search the mySQL Database using PHP. You can specify what kind of search with the radio buttons!

Wildcard = %__%; Suffix = %__; Prefix = __%...

Table of Contents

To see the subcategories of each, click on the arrows.

Content in the language

Other Languages & links

What is This and Why?

Basic Phrases and Structure

Pronunciation and Stress

Derivational Morphology and Rules

Verb Conjugations part 1

Verb Conjugations part 2

Words in Themes

Articles, Quantifiers, Pronouns, and Conjunctions

Conciseness of Words part 1

Conciseness of Words part 2

Borrowings from other Languages

Affixes and Word Roots

Suggest new words to be added!

COMING SOON! Your entries will be converted from HTML to JSON format

List of User Suggestions of New Words

Using AJAX, this button will get and display data from a JSON file.

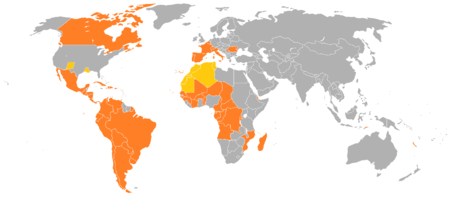

Romance Languages in the world and the Lingua Franca

About Romance Languages

If we combine all the native Romance speakers together, it would be about 11.5% of the world's population. If we also consider all the countries where a Romance language is official, it is astounding: 29 for French (about 200 million people who speak it), 20 for Spanish (442 million people who speak it), 10 for Portuguese (about 262 million who speak it). Overall about 1 billion people have some knowledge of a Romance language. It makes sense to establish an easier to learn, yet expressive, language uniting them. This bridge language would ease communication. Other people who don't speak a Romance language can also benefit from learning an easier "bridge" language. If we consider that English is 57% Romance (from Latin and French), English speakers would find it especially easier to learn over other languages.

The Lingua Franca

Like the Lingua Franca that existed around the Mediterranean, this lingua franca is not designed to replace any language. It could, however, facilitate friendship, understanding, and the propagation of knowledge. Valuable scientific ideas, techniques, technology, and philosophy could spread faster with this language. Voç Comune could be helpful in the developing world as well as the developed world. Using a common language, we could share ideas on global issues and try to solve them.

My intent was to create an expressive, concise (unambiguous), and artistic auxiliary

language. Unlike major romance languages, like Spanish, there isn't a grammatical gender for adjectives and nouns. Verb conjugations are also easier, because they are based only on the tense, not the subject! Like the auxiliary language "Esperanto", adjectives, verbs, and nouns are easily distinguished from each other. Unlike Esperanto, and more like Interlingua and Occidental (Interlingue), my constructed language is naturalistic

in form.

Because of the source languages and the ease in which to learn, the

Întermedjario is likely a good language to segue

into learning Spanish, French, and Portuguese.

What are some basic greetings and questions in the language?

How do you pronounce the vowels of this language?

If you have any comments or suggestions, please email me;

I'd like to hear from you. I've enjoyed the time that I've spent conducting research and refinement in this project.

By sharing with you, I hope that you enjoy the language as much as I do. After getting a feel for

my language, feel free to ask me any questions or make suggestions.

If you are impressed and feel compelled to donate, I accept Paypal.

Engratça!

Basic Phrases and Structure

Greetings and Phrases

Ola Hello

Aló Hello: when answering the telephone

Chi yes (sounds like 'she')

Ey yes, this is right/good

Axá yup, I hear you, keep going

na no

¿Favlam-vus ___? Do you speak ___?

Jo favlam ___. I speak ___.

bon djorn good day

bon mañá good morning

bon targi good afternoon

bon suara good evening

bon notchi good night

supley o por favor please

de nada You're welcome. It literally means "It was nothing."

Fui un plazi conocer-te Pleasure to make your acquaintance. It was a pleasure to meet you.

¿Como estam vus? o ¿Como vus estam? How are you? (formal or plural)

¿Como estam tu? How are you? (familiar)

Jo'stam bien. I'm fine. I'm well.

Jo'stam regulare. I'm so-so (or regular).

¿Como vus chamam vos? What do you call yourself? (What's your name?)

Jo me chamam ___. My name is___. I call myself ___.

¿De onde tu es? Where are you from?

Bon provetcho. Enjoy your meal.

Salú Bless you: wishing someone health and prosperity, especially after someone sneezes or when giving a toast at a gathering of friends and family.

¡Felicitaç! Congrats!

Desculpem-me Excuse me, pardon me (when getting someone's attention).

¿Podem-vus me yudar? Can you help me?... French: Pouvez-vous m'aider?... Spanish: ¿Me puedes ayudar?... Portuguese: ¿Pode me ajudar?

Jo'stam perdide. I am lost... Spanish: Estoy perdido... French: Je suis perdu.

¿Podríeb-jo vos yudar? Could/can I help you?... Spanish: ¿Podría ayudarle?... French: Puis-je vous aider?

Lo jo sentim.. I'm sorry (literally: I feel it)... Spanish: Lo siento.

Nus vay Let's go

Astê luego. See you later.

Tchau goodbye

Adeo Bye: meant to be used when you don't expect to see the other in a while (Literally: to God).

Bon viadj Bon voyage; have a safe journey.

How do you pronounce the vowels of this language?

Ways of saying thank you

Dangú. Thanks: when someone hands you something

Engratça. Thank you (kindly)

¡Engratça bocu! Thank you very much!

¡Obligadu! Thank you: I am very grateful and owe you a favor in return!

Sentence Structure and Plurality

Unlike most Romance languages, the adjectives do not need to be marked as plural— only the noun. To make a noun plural add [ z ] or [ ez ] to the end, instead of [ s ] or [ es ].

Typically, if a noun ends in a vowel, just add z. With the -en and -on suffixes, just add z. This is very much like Catalan, Galician, Portuguese, and French.

Examples:

orden -> ordenz (orders)

origen -> origenz (origins)

volumen -> volumenz (volumes)

egsamen -> egsamenz (exams, examinations)

médicien -> médicienz (medical doctors)

crimen -> crimenz (crimes)

imaxen -> imaxenz (images)

balcón -> balcónz (balconies)

pobulación -> pobulaciónz (populations)

camión -> camiónz (trucks)

percepción -> percepciónz (perceptions)

The typical sentence structure with pronouns is as follows:

Subject / indirect object / direct object / verb OR

Subject / indirect object / verb / direct object (If a pronoun, the direct object is attached to the verb)

What are the pronouns?

Usually adjectives will follow the noun as in most Romance languages, but they can also come before.

Questions that don't start with who, what, where, when, why, and how will start with the verb and the subject is attached.

What are the question words?

Basic Nouns, Adjectives, and Adverbs

Adjectives end in [ e ], [ ic ], [ al ], [ an ], [ il ], [ esc ], or [ bel ].

There are exceptions when it comes to the typical adjectival suffixes, such as the following comparatives:

mayor, menor, mellor, peor, superior, inferior.

Almost all adverbs end in [ mén ], which correlates to [ mente ] in Spanish and Portuguese.

Having these suffixes makes it easy to point modifying words out. Adjectives can come before or after the noun.

Many words can easily be made into other forms:

life (noun)= vida

vital (adj)= vital (D becomes T)

vitally (adv)= vitalmén

vitality (noun)= vitalitá

to revitalize (verb)= rivitalizar

revitalized (adj)= rivitalizade

revitalization (noun)= rivitalización

vitamin (noun)= vitamina

civil (adj)= civil

to civilize (verb)= civilizar

civilized (adj)= civilizade

civility (noun)= civilitá

civilization (noun)= civilización

is civilizing (as verb)= estam civilizandu

civilizing force (as adj)= força civilizatore

magnificent (adj)= magnífic

to magnify (verb)= magnifiçar

magnification (noun)= magnificación

sequence (noun)= secuença

sequential (adj)= secuenchal

sequentially (adv)= secuenchalmén

concept (noun)= conceptu

conceptual (adj)= conceptual

to conceptualize (verb)= conceptualizar

conceptually (adv)= conceptualmén

social (adj)= social

socially (adverb)= socialmén

socialism (noun)= socialismo

socialist (noun)=socialista

socialistic (adj)= socialistic

to socialize (verb)= socializar

socialized (adj)= socializade

socialization (noun)= socialización

society (noun)= societá

societal (adj)= societal

sociable (adj)= sociábel

sociability (noun)= sociabilitá

sociology (noun)= sociologíê

sociologic (adj)= sociologic

associate (verb)= asociar

associated (adj)= asociade

associate, member, partner (noun)= asociado

associative (adj)= asociative

association (noun)= asociación

different (adj)= diferente

difference (noun)= diferença

differently (adv)= diferentemén

intellect (noun)= intelectu

intellectual (adj)= intelectual

intellectual (noun)= intelectuau

intellectually (adv) = intelectualmén

Italy (noun) = Italia

Italian (adj) = italian

Italian (noun) = italiano

What about verb endings?

What are suffixes to make nouns into adjectives and vice versa?

Pronunciation and Stress

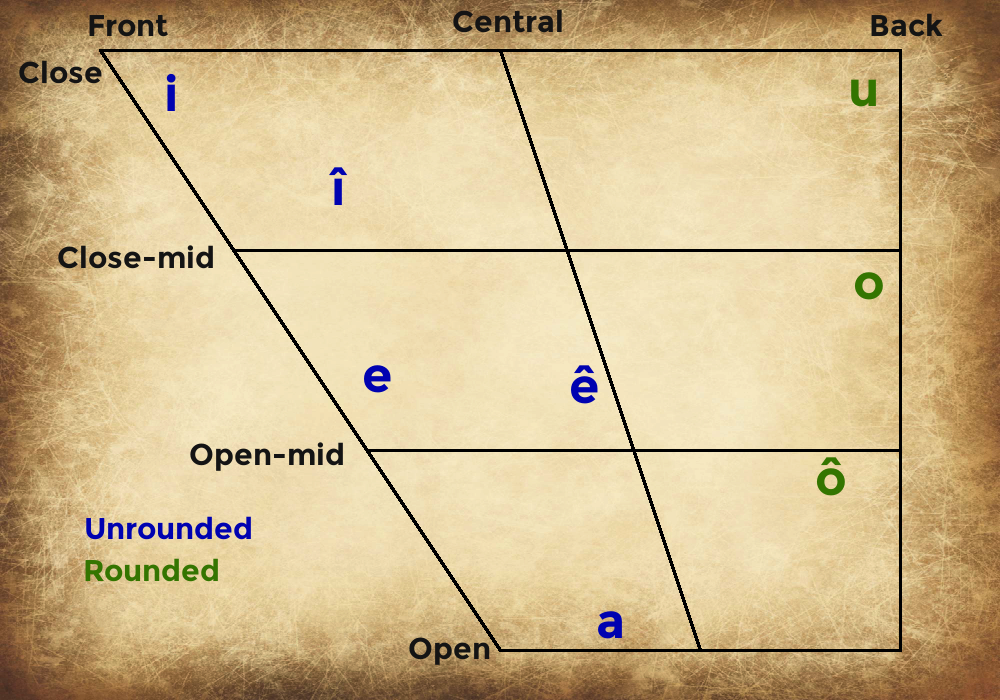

Vowels and Vowel Trapezoid

This chart shows the approximate location of the vowels using Voç Comune letters.

Vowels and the International Phonetic Alphabet:

[a] is usually pronounced as [a] in Spanish and Italian (IPA a and ä).

[e] is usually as in English [set] (IPA ɛ) or Catalan [afecta] but sometimes (IPA e) when stressed.

[ê] (IPA ɐ, ɜ) as some speakers of Portuguese "lâmina" (blade) and “aja” (act), Galician “feita” or leite, Catalan “amb” (with) or "metge", French "sort", German "herrlich" or "kommen". Note that most English dialects use IPA ʌ to represent the

vowel sounds in “but” or “young” but they are actually closer to central vowels like open-mid central unrounded vowel (ɜ) or near-open central vowel (ɐ).

There is no designation for roundness for ɐ, so it is similar to a schwa.

[i] is like English [ee] in [feed].

[î] (IPA ɪ) is short as in English [his] and German [bitte] or (IPA ɨ) as in Romanian [înspre] and European Portuguese [pequeno].

[o] is usually like the [o] in [social].

[ô] (IPA ɔ or rounded ɒ) as the [ough] in the word [thought], the [o] in Catalan [soc], the [a]

in Occitan [país], and the [a] in Swedish [jag]. It may approach the sound used in French [pas] but never nasal (IPA ɑ).

[u] is usually pronounced like [oo] in [food]. [U] can be pronounced as IPA ʊ when the syllable is unstressed.

[ei] (IPA eî) is pronounced like the [ey] in [they], the [a] in [fate], or [eigh] in [eight]. At the end of a word this can be rendered as in Spanish [ey] in [ley].

[au] is pronounced (IPA aʊ), like [ou] in English [out] or [cow], Brazilian Portuguese [mal].

[ou] is pronounced like [ow] in English [owe].

Jota, Zhe, Gee

Some words derived from Spanish with a J, have been changed to X since J has a different sound. In Voç Comune, J is always like the French and Portuguese pronunciation.

G before e and i matches the Italian and English pronunciation. It is also like TG of Catalan before e and i, or DJ in all positions.

Pronunciation of Other Letters with IPA

Other Consonants:

b, d, f, l, m, n, p, t, v, w, y: just like in English.

[ñ] [IPA ɲ / nj] represents Spanish [ñ], Portuguese [nh], French/Italian [gn], and English [ni/ny].

[j] (IPA ʒ) should be pronounced as in French, Portuguese, Catalan, and Romanian, or the [si] in English [delusion].

It is never like Spanish [j].

[x] (IPA X or ɦ or χ) is pronounced as Spanish [j]; it's never pronounced as [ks] or [kz]. **Note: [egs-] usually replaces [ex-].**

[r] (IPA ɾ) is an alveolar flap like Spanish [pero]. It is never like French guttural R or Spanish trilled/rolled R (perro).

[c] is pronounced like [s] before [e] or [i], otherwise like hard c.

[ç] is pronounced like [s] when the next letter is NOT [e] or [i]. IF the next letter becomes E, then it will change into a normal [c].

[g] is pronounced like English [j] before [e] or [i] (IPA dʒ and dʑ), otherwise like hard g.

[gh] replaces [gu] in English [guitar]-> Întermedjario [ghitara] in order to maintain the hard g sound before [e] or [i].

[h] can be pronounced but it's better to leave it silent as in Spanish, French, and Portuguese.

[qu] is pronounced the same as in Spanish and Portuguese [IPA k].

[k] (IPA ɢ) is like the [g] in French [grotte] (IPA: ɢʁɔt). This phoneme is commonly used in Arabic and Persian,

and is rarely used in Voç Comune. Please see: Voiced uvular Stop.

Digraphs and trigraphs:

[ll] (IPA ʝ or ʎ) is a digraph that is used in Spanish the same way as in this language. It can approach the pronunciation of IPA ʒ as in some Spanish dialects.

[ch] (IPA ʃ) is a digraph, same as [sh] in English [she] and [ch] in [machine]. The pronunciation of [ch] is the same in Portuguese and French.

[tch] (IPA tʃ) is a trigraph, same as 'ch' in English [chore].

The Tilde and Stressed Syllables

All languages have some syllables that are accentuated in a word or phrase. Some languages, such as the

English language, do not

mark which syllables are stressed in a word. Many romance languages do.

Like Spanish and Portuguese, Voç Comune uses the tilde (accent mark) on vowels to signify stress where it doesn't follow the normal rules.

However, words do not require the tilde, or the circumflex, to be understood. Remember that the circumflex is only used for pronunciation, not for stress.

Tildes and circumflexes can be left off as needed for quick communication.

The tilde and circumflex are almost always used for publications, though.

The normal rules:

Stress the penultimate (second-to-last) syllable if the word ends in any vowel except the dipthong AU. Also stress the penultimate syllable if the word ends in N or Z.

Stress the last syllable if the word ends in any consonant or AU. Do not stress the last syllable if the word ends in N or Z.

If the stress needs to be on a different syllable than the normal rules specify, use the tilde.

Examples:

înformación (information),

relaciónz (relations),

país (nation),

cartografíê (cartography),

cartógrafo (cartographer),

geográfic (geographic),

mañá (morning)

Z and Ç

paç = peace; paz (Spanish/Portuguese); paix (French); pace (Italian)

pacifiçar = to pacify; pacificar (Spanish); pacifier (French)

voç = voice; voz (Spanish/Portuguese); voix (French); voce (Italian)

vocez =voices

vociferante =vociferous

cruç = cross

crucez = crosses

Voç Comune uses a cedilla [ ç ] like Portuguese, French, and Catalan. A lot of times, the word will be recognizable if you know Spanish and use [ z ] in place of the [ ç ].

Either way it is pronounced the same way.

Remember that CI, ZI, CE, and CI are never pronounced as in some parts of Spain with a sound similar to English TH (IPA ð). This is called seseo/ceceo in Spanish.

The letter Z or EZ is used for the plural instead of S or ES as in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English or I or E as in Italian.

le casaz - las casas (Spanish) - le case (Italian) - the houses - os casas (Portuguese)

l'amigoz - los amigos (Spanish) - gli amici (Italian) - the friends - os amigos (Portuguese) - les amis (French)

le livroz - los libros (Spanish) - i libri (Italian) - the books - os livros (Portuguese) - les livres (French)

CH and QU

'Ch' is never pronounced as Italian 'hard c' before 'i' and 'e'.

The word for passion is pachón. This is a combination of Galician, Portuguese, and Spanish.

Galician: paixón, Portuguese: paixão, Spanish: pasión. In Portuguese and Galician, an x can be pronounced as sh in English and ch in French. This is not the case in this language,

X is always pronounced as Spanish J (slightly raspy H).

Qu is pronounced as English 'k' and is used simlarly to Spanish.

egsplicar - explain - explicar (Spanish/Portuguese)

queso - cheese - queso (Spanish) - queijo (Portuguese)

chocolati - chocolate - chocolate (Spanish/Portuguese) - xocolata (Catalan) - chocolat (French)

Derivational Morphology and Rules

Spanish and Portuguese Comparisons

Many words are the same or very similar to Spanish and/or Portuguese. Voç Comune simplifies some words in a way that doesn't detract from understanding.

Spanish -miento and -mento are always -mento which is like Portuguese.

sufrimento = Spanish sufrimiento and Portuguese sofrimento

fundamento = Spanish/Portuguese fundamento

Spanish -ble(-bles) and Portuguese -vel(-veis) = -bel which means capable, possible, and/or ability.

responsábel (responsible) is responsable in Spanish and responsável in Portuguese.

susteníbel sustainable (from sustener to sustain)

indicíbel unspeakable, unutterable

inegsorábel inexorable

-bilitá -bility (noun)

sustenibilitá sustainability - sustentabilidade (Portuguese) - sustentabilidad (Spanish) - sostenibilità (Italian)

Spanish -ción(-ciones), Portuguese -ção(-ções), Catalan -ció(-cions), and French/English -tion(-tions) = -ción(-ciónz).

Spanish -sión and Portuguese -ssão = -sión (English -sion/-ssion).

This suffix makes nouns from verbs, denoting result (as a whole) or resulting state, or manner of action.

construcción construction, the process of building together (construir to construct)

înuvación innovation

ambición ambition

alusión allusion

aprensión apprehension

Because the main adjectival suffix in Voç Comune is E, nouns that end in E are changed to I or EY.

Spanish análisis and Portuguese análise = análisi

The O and A endings found in adjectives in Spanish and Portuguese are dropped or replaced with an E. *Noun and adjectival agreement does not exist.*

What are the adjectival suffixes?

Spanish -anza and Portuguese -ança = -ança.

esperança (hope)

aliança (alliance)

Spanish -ancia and Portuguese -ância = -ança.

împortança (importance)

Spanish -encia and Portuguese -ência and -ença = -ença.

presença (presence)

esença (essence) becomes esenchal (essential) for the adjectival form. *pronounced as in Engish*

potença (power, potence) -> potenchal (potential)

Spanish -esa/-iz/-isa that denotes the feminine, like -ess in English = -iç.

actriç (actress) and actricez (actresses).

In Spanish, it's actriz and actrices; in Portuguese, it’s atriz and atrizes; in Italian, it’s attrice and attrici; in French, it’s actrice and actrices; in Romanian, it’s actriţă and actriţe

Spanish and Portuguese -ar (adjective ending) and -aria,-ario (adjective endings) = -are (of, like, related to, pertaining to). This originally came from Latin -āris.

circulare = circular (from circul - circle)

solare = solar (from sol - sun)

celulare = cellular (from celul - cell)

-al -al: of, like, related to, pertaining to. This originally came from Latin -ālis and is used when the stem doesn't contain an 'L'.

conceptual conceptual (conceptu concept)

social social

*For nouns, the AL ending becomes AU*

Spanish animales and Portuguese animais (both meaning animals) = animauz.

Spanish and Portuguese -ificar = -ifiçar. This suffix forms verbs, from adjectives, indicating process of causing an object to gain the given characteristic; make something something else or transform or convert into. When making the noun or participle forms, the C cedilla becomes a hard C (when adding -ifición, -ificadu).

clarifiçar (clarify)

clarificación (clarification)

Most adjectives in Spanish and Portuguese match the noun in that they end with a or o. However, in Voç Comune, the endings don't change based off of the noun by gender nor number.

dictadorez rique for dictadores ricos (Spanish), ricchi dittatori (Italian), ditadores ricos(Portuguese), riches dictateurs (French).

Spanish Hue- is rendered as O- or Ue-

The word for orphan is órfano, órfana. As you can see, it is easy to understand based on other romance languages. Did you notice that Catalan, Portuguese, and Spanish has an accent on that first vowel? In Spanish many words that began with o became an hue. In Portuguese, the -an- became nasalized to -ã-. The -ph- originally came from Greek and was pronounced like an aspirated p. This pronunciation later changed to f, but is still spelled the old way in English and French.

Italian: orfana, orfano; French: orphelin, orpheline; Romanian: orfan; Catalan: òrfena, orfe; Galician: orfa, orfo;

Portuguese: órfão, órfã; Spanish: huérfana, huérfano; Latin: orphanus

The word for labor strike is folga.

Galician: folga and Spanish: huelga

Many words in Spanish, originally had an f in place of the h, but over time it was dropped. For both huérfana and huelga, Spanish uses hue- which replaced the original stressed o.

The word for egg is uevo.

Spanish: huevo, Portuguese: ovo, Italian: uovo, French: oeuf

However, the word for ovary, ovario, starts with ov- instead of uev- and this is noted in the dictionary.

Spanish: ovario, Portuguese: ovário, French: ovaire, Catalan: ovari

M or N before F?

Words in English spelled sym- include the word symphony which is simfoníê. Some languages use sin- and others use sim- or sym-: Spanish sinfonía, Catalan: simfonia, French: symphonie, Italian and Portuguese: sinfonia... Note: While the word symphony in Spanish is spelled sinfonía, the N is pronounced as an M before F. This pronunciation goes for other words, like anfibio amphibian, as well, so in this language the pronunciation is the same as Spanish but the letter written is M.

Transforming Nouns into Adjectives (and vice versa)

Spanish -dad/-tad, Portuguese -dade, Italian -tà, French -té and English -ty is always -tá

libertá (freedom, liberty) is the same in Spanish, but is liberdade in Portuguese. It comes from the adjective libre. Many adjectives that end in -re become -er- before adding -tá. These are noted in the dictionary.

complejitá (complexity) is complejidad in Spanish and complexidade in Portuguese. It comes from the adjective compleje. The -e becomes -i-.

responsabilitá (responsibility) is responsabilidad in Spanish and responsabilidade in Portuguese. It comes from the adjective responsábel. The -bel becomes -bili-.

You can add AL directly to a word ending in -ción.

nación + AL = nacional (national)

An adjective ending in -al always requires an -i- before adding -tá (Spanish -dad, Portuguese -dade).

nacional + I + TÁ = nacionalitá (nationality)

This is also true of -il: fácil (easy) + I + TÁ = facilitá

When attaching TÁ to make a noun from an adjective ending in E, the E will become I unless the adjective ends in IE.

verace (truthful, veracious) drop E + I + TÁ = veracitá (truthfulness)

socie (Latin root) + TÁ = societá (society) - in this case it does not change.

If a verb ends with -IR, but has an E before it, The I needs an acute accent.

creír, posseír

Using Participles and Gerunds

Present Participles and Gerunds

Present Participles are derived from verbs and end in -nte for adjectives and -nti for some nouns.

The gerund is a verb form which has an adverbial function, not an adjectival function like a participle,

nor a noun function like an infinitive. The gerund ends with -ndu.

cantante - (adj) singing [le páxaro cantante - the singing bird]

cantandu - (gerund) singing

escrivente - (adj) writing [le machina escrivente - the writing machine]

escrivendu - (gerund) writing

traduciente - (adj) translating

traduciendu - (gerund) translating

How do I use the gerund for the continuous verb tense?

Past Participles

Past participles can be adjectives or used in the formation of perfect tenses. The regular forms will end with -de as an adjective and -du as a verb conjunctive.

cantade - (adj) sung (from cantar)

retenide - (adj) retained (from retener)

traducide - (adj) translated (from traducir)

These are rendered as cantadu, retenidu, traducidu after the verb haver.

How do I use the past participle with haver for perfect tense verbs?

Some nouns can be made by changing the -de to a -do or -da. This becomes the receiver of the action of the verb root.

acusado - the accused, defendant (acusar - to accuse)

pechado - caught fish (pechar - to fish)

Some past participles are irregular, as in Spanish, French, Catalan, and Portuguese.

[Infinitive -> Past participle] Examples:

dicer (tell, say) -> ditchu

pridicer (predict) -> priditchu

obrir (open) -> obertu

murir (die) -> mortu

facer (do) -> fetchu

desfacer (undo) -> desfetchu

volver (turn) -> voltu

devolver (return, give back) -> devoltu

envolver (involve, wrap up in) -> envoltu

absolver (aquit) -> absoltu

resolver (resolve)-> resoltu

poner (put, place) -> postu

împoner (impose, instill) -> împostu

cubrir (cover) -> cubertu

descubrir (discover) -> descubertu

romper (break) -> rotu

escriver (write) -> escritu

descriver (describe) -> descritu

înscriver (sign up, enroll, inscribe) -> înscritu

suscriver (subscribe) -> suscritu

ver (see) -> vistu

satisfacer (satisfy) -> satisfetchu

încurrer (incur, commit) -> încursu

Some have the possibility of a regular form and an irregular one.

omitir (omit)-> omisu , omitidu

insertar (insert)-> insertu, insertadu

împrimir (print) -> împresu, împrimidu

elegir (choose) -> electu, elegidu

prover (provide) -> provistu, providu

salvar (save) -> salvu, salvadu

Some have an adjective (irregular past participle) that is different than the verb conjunctive.

bendicer (bless) -> bendite, bendicidu

confundir (confound, confuse) -> confuse, confundidu

despertar (wake up) -> desperte, despertadu

maldicer (curse, swear) -> maldite, maldicidu

posseír (possess, own) -> possese, posseídu

presumir (presume) -> presunte, presumidu (Note: presumción - presumption)

suspender (suspend) -> suspense, suspendidu

naicer (be born) -> nate, nacidu

limpar (clean) -> limpe, limpadu

payar (pay) -> paye, payadu

juntar (join together) -> junte, juntadu

gastar (spend, consume) -> gaste, gastadu

egstinguir (extinguish) -> egstinte (extinct), egstinguidu

corromper (corrupt) -> corrupte, corrompidu

Verb Conjugations

Introduction to Verb Conjugations

Verbs are not conjugated based on the subject as in most Romance languages.

There is only one form for each tense, except for ser which has two in the present tense.

The subject must always come before the verb in order to know who is doing the action unless it is implied by the previous sentence.

The infinitive is like Spanish and Portuguese, ending in -ar, -er, or -ir.

Most verbs are regular in that they are conjugated the same way by tense. There are a few exceptions that are based mainly on composite equivalents in Spanish and Portuguese.

Present

Present tense ends in -m. It can be used for ongoing actions in the present,

as well as an action that will happen soon.

cantam: sing, sings, am/is/are singing (from the infinitive cantar).

escrivem: write, writes, am/is/are writing (from the infinitive escriver ).

traducim: translate, translates, am/is/are translating (from the infinitive traducir).

To negate a verb, simply place na in front of it.

na cantam: don't sing, doesn't sing

na escrivem: don't write, doesn't write

na traducim: don't translate, doesn't translate

Simple Past

Simple Past (Preterite) ends in -oú if an -ar verb, -eú if -er verb, and -iú if -ir verb. It describes a single event at a particular time in the past.

cantoú: sung (from the infinitive cantar)

escriveú: wrote (from the infinitive escriver)

tradujú: translated (from the infinitive traducir)

Imperfect

The imperfect tense is used as in other Romance languages.

The imperfect is used to express an action or state viewed as being in progress in the past,

or to describe what happened periodically/repeatedly in the past, or something that started in the past

and continues into the present.

The Imperfect ends in -va for -ar verbs and

-ha for -er and -ir verbs.

cantava: used to sing, was singing (from the infinitive cantar)

escriveha: used to write, was writing (from the infinitive escriver)

traduciha: used to translate, was translating (from the infinitive traducir)

Jo'stava cocinandu cando le telefono sonoú. I was cooking when the telephone rang.

Note: Jo'stava is the contraction of Jo estava.

Future

Future tense ends in -rá.

cantará: will sing (from the infinitive cantar)

escriverá: will write (from the infinitive escriver)

traducirá: will translate (from the infinitive traducir)

Irregular forms:

fará: will do/make (from the infinitive facer)

dirá: will say/tell (from the infinitive dicer)

To say "going to" (for the immediate future), one uses the word vama with the infinitive of the verb:

Jo vama cantar: I am going to sing.

Ella vama escriver: She is going to write.

Ellez vama traducir: They are going to translate.

Conditional

Conditional is usually translated as would, could, must have, or probably, to express probability, possibility, or wonder.

The conditional tense ends in -ríeb.

cantaríeb: would/could sing (from the infinitive cantar)

escriveríeb: would/could write (from the infinitive escriver)

traduciríeb: would/could translate (from the infinitive traducir)

Irregular forms:

faríeb: would do/make (from facer)

diríeb: would say/tell (from dicer)

traríeb: would bring (from trazer)

Essential nature versus state or condition

There are two copulas in Voç Comune, as in Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan.

Ser is used for characteristics, including age, and estar is used for states of being (feeling and appearance).

Ellez som velle. They are old.

El estam velle. He is looking old.

Jo'stava machu fambiente. I was very hungry. (jo'stava= jo estava)

El estam en ira. He is angry (in anger).

Nus estam aborride iquí. We are bored here.

Locations

Ser is used for permanent locations. Estar is used for transient locations and where people are located.

El estam dêntro dele casa. He is in the house.

Jo'stam en casa. I am at home. (jo'stam = jo estam)

Mev casa es dêntro dele ciudad. My house is in the city.

Passive voice

Ser is used to form the passive voice with a past participle with an ending of de

Estar is usually used with adjectives that derive from past participles of verbs since the use of ser

would sound like a verb in the passive voice.

Active voice = Jo comem pitza. I eat pizza.-> Passive voice = Le pitza es comide per mi. The pizza is eaten by me.

Le pitza fui comide per ellez. The pizza was eaten by them.

Le veritá fui egsposte The truth was exposed.

Perfect tenses

haver: 'to have' is used in auxiliary forms for the perfect tenses only. The present tense of haver is hau.

Present perfect denotes something that took place prior to the present moment.

El hau manjidu. He has eaten. (manjer = to eat or munch on)

Jo hau escritu le livro. I have written the book.

Present perfect continuous denotes something that started in the past and has continued up until now. haver + estadu +

present participle gerund

Jo hau estadu tocandu le ghitara por dos uoras. I have been playing guitar for 2 hours.

Past perfect denotes something that took place prior to a moment in the past.

El haveha manjidu. He had eaten.

Future perfect denotes something to take place prior to a moment in the future

El havrá manjidu. He will have eaten.

Conditional perfect denotes something conceived as taking place in hypothetical past circumstances.

El havríeb manjidu. He would have eaten.

What are the words that end with -ndu or -du?

Progressive and Continuous

Progressive (continuous) tenses are rendered with the auxiliary verb estar plus the present participle gerund.

Jo'stam lesiendu un livro eccelente. I am reading an excellent book.

El estuvi mirandu le televizión. He was watching television.

Demañá , jo'stará conduciendu mev carro por doce uoras. Tomorrow, I will be driving my car for 12 hours.

Subjunctive and Imperative

The subjunctive mood is used to express uncertainty, doubt, and/or subjectivity. So anything that starts with an opinion, such as:

It's possible that, It's good that, It's important that, I want (that), I hope (that), I feel (that), and so on, will use the subjunctive tense.

The present subjunctive is also used for the command form, otherwise known as the imperative.

Subjunctive (present): Like Spanish and Portuguese, the vowel changes. One changes the -er or -ir to -am; and the -ar to -em

cantem: sings, sing (from the infinitive cantar)

escrivam: writes, write (from the infinitive escriver)

traduzcam: translates, translate (from the infinitive traducir)

Nus querem que vengam Josef. We want that Joseph comes or We want Joseph to come.

¡Cantem! Sing!

¡Nus cantem! Let's sing!

Subjunctive (imperfect): -ssê

cantassê: sings, sing (from the infinitive cantar)

escrivessê: writes, write (from the infinitive escriver)

tradujessê: translates, translate (from the infinitive traducir)

Irregular cases of Ser, Estar, and ir: to be and go

Infinitive to be = ser.

Present tense is/am/are = som and es. 'Som' should be used with plural subjects (they, us...) and 'Es' is used with singular subjects (I, he, she, it...).

Perfect past was/were = fui.

Imperfect was/were (ser) = era.

Imperfect subjunctive was/were (ser) = fuissê.

Present subjunctive of ser = seyam

Infinitive to be (temporary) = estar.

Preterite (perfect past) was/were (estar) = estuvi.

Imperfect subjunctive of estar = estuvessê.

When do I use estar versus ser?

In Spanish and Portuguese, ser and ir share some of the conjugations. To get rid of ambiguity, ser and ir

do not share those conjugations.

Infinitive to go = ir.

Present tense of ir, go/goes = vam

Preterite (perfect past) of ir, went = anni.

Imperfect past of ir = iva.

Present subjunctive of ir = vayam.

Imperfect subjunctive of ir = anniessê.

Past Participle of ir, gone = idu.

Present Participle (gerund) of ir, going = yendu.

Irregular cases of Facer, Poner, Querer, and Tener

Present tense do/does = faç.

This comes from =

French: faisons, font, fais, fait, faites

Portuguese: faz, faço, fazes, fazeis, fazem

Spanish: hace, Hago, haces, hacemos, hacéis, hacen

Catalan: faig, fas, fa, fem, feu, fan

Galician: fago, fas, fai, facemos, facedes, fan

Italian: faccio, fai, fa, facciamo, fate, fanno (italian)

Perfect Past (Preterite) did, made, took action in some way = fici (from infinitive facer).

This comes from =

Spanish: hice, hiciste, hizo, hicimos, hicisteis, hicieron

Portuguese: fiz, fizeste, fez, fizemos, fizestes, fizeram

Catalan: fiu, fieres, féu, férem, féreu, feren

Galician: fixen, fixeche, fixo, fixemos, fixestes, fixeron

French: fis, fit, fît, fîmes, fîtes, firent

Italian: feci, facesti, fece, facemmo, faceste, fecero

Imperfect Subjunctive of facer = ficiessê

This comes from =

Spanish: hiciera, hiciese, hicieras, hicieses, hiciera, hiciese, hiciéramos, hiciésemos, hicierais, hicieseis,

Portuguese:fizesse, fizesses, fizéssemos, fizésseis, fizéssem

Catalan: fes, fessis, fes, fèssim, fèssiu, fessin

French: fisse, fisses, fît, fissions, fissiez, fissent

Present Subjunctive of facer = fagam

This comes from =

Spanish: haga, hagas, hagamos, hagaís, hagan

Galician: faga, fagas, fagamos, fagades, fagan

Portuguese:faça, faças, façamos, façais, façan

Catalan: faci, facis, fem, feu, facin

French: fasse, fasses, fassions, fassiez, fassent

Perfect past wanted = quisi (from infinitive querer).

Preterite (perfect past) of poner (to put) = pusi.

Note: other verbs that end in -poner will use the same ending -pusi.

Preterite (perfect past) of tener (to have, hold) = tuvi. Note: other verbs that end in -tener will use the same ending -tuvi.

Irregular cases of Haver, the auxiliary verb

Haver, like Spanish haber, is only used as an auxiliary verb.

Present tense have/has = hau.

Perfect past had = huvi.

When do I use haver?

Reflexive

A verb is reflexive when the subject and the object are the same. The reflexive pronoun can be placed before the verb or it can be attached to the end of the verb with a '-'. Se is generally translated as self.

Ella se presentam. She presents herself.

Ella presentam-se.

Jo me presentam. I present myself.

Jo presentam-me.

Reflexive (and reciprocal) pronouns by subject:

Jo -- me

Tu -- te

Vus -- vos

Ela, El, Ell, Ilu, Ellez, Ellaz, Iluz -- se

Nus -- nos

The reflexive pronouns are the same in Spanish, except the 'vus' (vosotros) one is 'vos' (not os). Note that they match up with the direct objects, except Ella, El, Ell, Ilu, Ellez, Ellaz, Iluz is 'se'.

Examples:

Jo me ducham. I shower (myself). [In Spanish: (Yo) me ducho.]

Vus vos ducham. You (all) shower (yourselves). [In Spanish: (Vosotros) os ducháis.]

Nus nos vem cada día. We see each other every day. [In French: Nous nous voyons tous les jours.]

Ella se levam. She is getting up. [In French: Elle se lève.]

Ellez se suntchim. They kiss each other (one another). [In Spanish: (Ellos) se besan.]

Differences from Spanish "se"

Voç Comune has no "passive Se" as in Spanish:

Se escribe el libro en español. (The book is written in Spanish.)

It is constructed more like French:

Le livre est écrit en espagnol.

Voç Comune version is:

Le livro es escrite en español.

In Spanish: "se construyó en un año." (It was built in a year.)

becomes "(il) fui construide en un añu."

"Om" in Întermedjario takes the place of "impersonal Se" in Spanish:

"se puede comprar limones en el mercado" becomes

Om podem comprar limónz en le mercado. (One can buy lemons at the market. Or You can buy lemons in the market.)

Spanish "¿Como se dice X?" becomes ¿Como om dicem X? or ¿Como dicem-om X?

(How do you say X?)

Words in Themes

Numbers

Numeroz

cero, nul zero, 0

uno one, 1

dos two, 2

tres three, 3

catro four, 4

cincu five, 5

seis six, 6

sete seven, 7

otcho eight, 8

nove nine, 9

dieç ten, 10 [dec-]

*uno-decime 1/10, one-tenth

*numero decimal, decimau decimal number

unce eleven, 11

doce twelve, 12

trece thirteen, 13

catorce fourteen, 14

quince, cincuce fifteen, 15

seice sixteen, 16

setece seventeen, 17

otchoce eighteen, 18

novece nineteen, 19

vinte, dosenta twenty, 20

treinta thirty, 30

cuarenta forty, 40

cincuenta fifty, 50

seisenta sixty, 60

setenta seventy, 70

otchenta eighty, 80

noventa ninety, 90

cento one hundred, 100

dos-cento two hundred, 200

tres-cento three hundred, 300

dos-mill two thousand, 2000

deci-mill ten thousand, 10000

cento-mill one hundred thousand, 100000

millón million

cincu-milló five million

billón billion

fracción = fraction

cifra = code (cipher)

digit = a number 0-9

Colors

Colorez

verde green

blave blue

brune brown

amaril yellow

jaloe yellow (between yellow and light orange)

blanche off-white

alve white

ruje red

porple purple

oranje orange

grise gray, grey

nerre black

cerele cerulean

azule sky blue (between cyan and blue)

turquese turquoise

ore gold (color) *ora gold

argente silver (color) *argenti silver

multicolore multicolored

escure dark *obscure obscure

clare clear, lightened/light *blave clare, clar-blave light blue

Parts of the Body

pela = skin

cabello = hair (head of)

abrigo de pela(z) = furcoat

peladj = skins of animal, fur

cara = face (front part of the head including the mouth, nose, and eyes)

denti = tooth

neris = nose

buca = mouth

orella = ear

oulo = eye

lengua = tongue (sometimes language of group)

braso = arm (of person)

antebraso = forearm

codov = elbow

perna = leg (of person)

rodilla = knee

pata = leg (of insect, animal)

pied = foot

manu = hand

dedo = finger, digit

dedo de pied = toe

petcho = chest, breast

pestana = eyelash

barba = beard

mustach = mustache, moustache

Family, Relatives, and People

mullêr, fêmina - woman, female (noun)

homen, másculo - man, male (noun)

bebí - baby

neño - boy

neña - girl

neñoz - children, kids

joven - youngster, young man or woman

adolescenti - adolescent, teenager

adulto - adult

esposo, esposa - spouse, husband, wife

casar - to get married

casade, maride - married (adj)

casa - household, house where family lives

familia - family

padrê, papi - father, dad, daddy

madrê, mama, mami - mother, mom, mommy

fillo - son

filla - daughter

irmano - brother (biological)

irmana - sister (biological)

cuzin - cousin (any relation)

primo, prima - first cousin

segundo, segunda - second cousin

nefot - nephew

nefota - niece

oncul - uncle

tanti - aunt

cuñad - brother-in-law

cuñada - sister-in-law

nora - daughter-in-law

ginro - son-in-law

sugro - father-in-law

sugra - mother-in-law

abula - grandmother, grandma

abulo - grandfather, grandpa

bis- (in names of kinship) great-

bis-abula - great grandmother, great grandma

bis-abulo - great grandfather, great grandpa

nieto - grandson

nieta - granddaughter

bis-nieto - great grandson

bis-nieta - great granddaughter

fra'ri - brother in organization (unrelated brother)

soror - sister in organization (unrelated sister)

señor - sir

señora - ma'am

mev'sêr i meusêr - sir (really polite), literally: my sir. In French, it is monsieur.

mev'dama i meudama - ma'am, madam (really polite, use for a woman of authority).

More than Happy and Sad, Good and Bad

bone = good (adjective) *Bone is shortened to Bon when wishing someone something.

Bon mañá = Good morning

bien = well (adverb)

alegre = cheerful, lively

tranquil = at ease, happy, tranquil

jole = lovely, nice, jolly

felice = happy, contented *Felice is shortened to Feliç when wishing someone something. Feliç Añu Nuve! = Happy New Year!

meravilla = marvel (noun)

meravillose = marvelous, wonderful (adjective)

delici = delight, allure (noun)

deliciose = delicious (adj)

triste = sad, miserable

mauve = bad, poor, inept (adjective)

mau = badly, adversely, dangerously (adverb)

malici = malice, ill will, wickedness, maliciousness

maliciose = malevolent/malicious

malvole = malevolent

malvolesa = malevolence

The Realm of Politics and Foreign Affairs

Le Domein dele Politica i l'Afeirs Egsteriore

ambajador - ambassador (French ambassadeur; Romanian ambasador; Italian ambasciatore; Spanish embajador; Portuguese embaixador;)

ambajada - embassy (Spanish embajada; Portuguese embaixada; French ambassade; Italian ambasciata; Romanian ambasadă)

atachey - attaché (French/English/German/Spanish)

charj-dafeirs - chargé d'affaires (from French/English) - a subordinate diplomat who substitutes for an absent ambassador or minister

cordon sanitare - cordon sanitaire (from French, meaning sanitary line, a policy of containment directed against a hostile entity or ideology)

colp de estat - coup d'étate (from French, meaning blow of state)

sargento - sergeant (French sergent; Portuguese/Spanish sargento)

multinacional - multinational

relaciónz înternacional - international relations

transnacional - transnational (affecting several countries)

supranacional - supranational (involving more than one country)

tôo - thaw (an improvement in the relationship between two countries; French dégel)

tributo - tribute (in the past, money or other things that a leader had to give to a more powerful leader)

Aldea global - global village (the modern world in which all countries depend on each other and seem to be closer together because of modern communications and transport systems).

país desvelopide - developed country

país en desvelopimento - developing country

mundiorden - world order (the political, economic, or social situation in the world at a particular time and the effect that this has on relationships between different countries)

raprochimento - rapprochement (the development of greater understanding and friendship between two countries or groups after they have been unfriendly)

normalizar le relaciónz - to normalize relations

chêtol-democraciê - shuttle democracy (political activity in which someone makes frequent journeys between two countries and talks to each government in order to end a disagreement or war)

amistá - friendship, amity, friendly relations (Spanish amistad; French amitié; Portuguese amizade)

amistose - friendly, amicable (has a good relationship with)

pocu amistose - unfriendly (an unfriendly country doesn't have a good relationship with your country)

Articles, Quantifiers, Pronouns, and Conjunctions

Articles (a, an, the) and Demonstratives (this, that, these, and those)

The definite article - English the, Portuguese o/a, and Spanish/Catalan el/la - is always le. Like English, there is no plural form - Spanish los/las, Catalan els/les, and Portuguese os/as.

The indefinite article - English a/an, Portuguese um/uma, Spanish/Catalan un/una, and French un/une - is always un.

Unez is the plural form and means some - Spanish unos/unas, Catalan uns/unes, Portuguese uns/umas, and French des.

Le pintura mi custoú unez mill euroz. - The painting cost me around a thousand euros.

Anytime le (the) is used in English, a definite article will surely be used in Voç Comune. However, like other Romance languages, Voç Comune will use a definite article when English uses no article at all. This includes times when a group of nouns is referred to in its entirety. For example, when blanket statements are made about all dogs, all humans, or all cars. Use the definite article with abstract nouns (or a noun referred to in a general sense), like peace, war, love, poetry, science, philosophy.

Demonstratives are used to point a particular item or items.

This (something close to the speaker) -> Este is the adjective form and esto is the noun form.

That (something away from the speaker) -> Esse is the adjective form and esso is the noun form.

That over there (something further away from the speaker) -> Quelle is the adjective form and quello is the noun form.

Only the noun form is made plural: these (things) -> estoz; those (things) -> essoz; those (things) over there-> quelloz.

Contractions: Combined Words

De and Le

1. If the word after LE begins with a vowel, LE becomes

L' and attaches to the noun.

2. If after step 1, there is DE followed by LE, it becomes DELE.

Note: This rule is similar in the Catalan language.

Examples:

dele mesa

de l'espritu, not del'espritu

dele human, not del'human

A and Le

Follow the same rules for De and Le above. If Le is not attached to the next word (because of a vowel),

it becomes ALE.

It is like Spanish AL and Italian al, allo, alla.

Examples:

ale restoranti

a l'universitá, not al'universitá

a l'escola, not al'escola

Jo

The subject pronoun for I can be attached to the verb if it starts with a vowel. All you do is drop the O in Jo for J'.

Examples:

Jo hau venidu

J'amam

J'abrasoú

Note: Portuguese, Italian, and French have many other article and prepositional contractions.

This language is more conservative like Spanish.

Portuguese: desta, deste, destas, destes = de este

desse, dessa, desses, dessas = de esse

no, na, nos, nas = en le

num, numa, nuns, numas = en un

Italian: col, coi = cun le

Pronouns and their Usage

Like other Romance languages, Voç Comune distinguishes subject pronouns from object pronouns and prepositional pronouns. There are also possessive pronouns which show ownership.

The subject (the nominative) is who is doing the action of the verb. The direct object (the accusative) follow transitive verbs and receive the action of that verb. Indirect objects (the dative) usually get the direct object. Prepositional pronouns are used after a preposition. The possessive (the genitive) comes before the noun. My house is mev casa or casa miyo house of mine.

1st person singular: I/me

Subject: Jo

Direct Object: me

Indirect Object: mi (to me)

Prepositional: mig

Possessive: mev (my), miyo (mine, of mine)

1st person plural: We/us

Subject: Nus...One can distinguish between inclusive and exclusive 'we':

Inclusive (includes the speaker and addressee) = Nucanchi

Exclusive (includes the speaker and Not the addressee) = Nusor

Direct Object: nos

Indirect Object: nois (to us)

Prepositional: nosó

Possessive: nosre (our), nosro (ours, of ours)

2nd person singular/informal: You

Subject: Tu

Direct Object: te

Indirect Object: ti (to you)

Prepositional: tig

Possessive: tev (your), tuyo (yours, of yours)

2nd person plural/formal: You; You all/You guys/Ya’ll

Subject: Vus

Direct Object: vos

Indirect Object: vois (to you)

Prepositional: vosó

Possessive: vosre (your plural), vosro (yours plural, of yours)

3rd person singular masculine: He/him

Subject: El

Direct Object: lo

Indirect Object: lli(used for both masculine and feminine; to him/her)

Prepositional: el

Possessive: su (used for both male, female, and inanimate), suyo (his, of his)

3rd person singular feminine: She/her

Subject: Ella

Direct Object: la

Indirect Object: lli (used for both masculine and feminine; to him/her)

Prepositional: ella

Possessive: su (used for both male, female, and inanimate), suya (hers, of hers)

3rd person singular inanimate object: It

Subject: Ilu

Direct Object: lu

Indirect Object: lli

Prepositional: ilu

Possessive: su (its), suyo (of it)

3rd person plural masculine/feminine/inanimate: They/them/their

Subject: Ellez/Ellaz/Iluz

Direct Object: loz/laz

Indirect Object: lliz (used for both masculine and feminine; to them)

Prepositional: ellez/ellaz/iluz

Possessive: suz (used for both male, female, and inanimate), suyoz, suyaz (theirs plural)

Intensifiers and Quantifiers

machu = very, quite.

It comes before an adjective or an adverb and takes the place of Spanish muy. It is an adverb.

Mev noiva es machu inteligente.

My bride is very intelligent.

Mev irmanaz som machu alte.

My sisters are very tall.

Tu favlam Voç Comune machu bien.

You speak Voç Comune very well.

bocu = a lot(of), much, many.

It takes the place of Spanish mucho/muchos and can be in front of a noun or after a verb.

When modifying a noun add de to make it an adjective.

Il chuvam bocu.

It rains a lot.

El hau comidu bocu.

He has eaten a lot.

Nus tenem bocu de treballo.

We have a lot of work.

Ella estudam bocu.

She studies a lot.

pocu = the opposite of bocu: little, few, or not much.

Il chuvam pocu.

It rains a little (not much).

Ella hau comidu pocu.

She has eaten little.

Vus tenem pocu de treballo.

You have little work.

algú = some, certain. This is used like Spanish algún and Portuguese algum/a, alguns, and algumas

Jo perdeú mev llaviz en algú luoga.

I lost my keys somewhere. (in some place)

¿Tenem-vus algú pregunta?

Do you have any questions? [Literally: Do you have some (a certain) question?]

ningú = any (when used in negative sentences) [like Portuguese: nenhuns, nenhumas; Spanish: ningún, ninguna].

Jo na tenem ningú aranja(z).

I don't have any oranges.

cualquel - any (used in affirmative sentences), whichever, no matter which [like

Portuguese: qualquer; Spanish: cualquier, cualquiera; Catalan: qualsevol].

Cualquel de esse livroz me parecem bien.

Any of these books seem good to me.

todo = all, whole, every. This is used as an adjective, but is before the article le.

Todo l'aula

The whole class

Todo mev cachorez

All my dogs.

Todo le livroz

All the books; Every book.

tudo = everything, all. This is used as a pronoun.

Jo querem comprar tudo.

I want to buy everything.

nada = anything, nothing (negative) [like Spanish and Portuguese: nada].

Nus sabem nada de ella.

We don't know anything about her. [We know nothing about her.]

algú cosa - anything, something (questions)

cualquel cosa - anything (positive), something

en/a ningú luoga - anywhere (negative sentences), no place, nowhere (adv)

en/a algú luoga - anywhere, somewhere

en/a cualquel luoga - anywhere, any place

Nus vay a cualquel luoga

Let's go anywhere (to any place)

algom - anybody/somebody (questions)[like Portuguese: alguém; Spanish: alguien; French: quelqu’un].

ningom - anyone, anybody (in negative sentences), nobody [like Portuguese: ninguém; Spanish: nadie].

cualquelom - anybody (any which person)

semprê o touju - always

Portuguese: sempre; Spanish: siempre; Catalan: sempre; French: toujours

nunca - never (something that has not happened yet)

jamás - never (more emphatic)

a vecez - sometimes, at times

tambí - also, too

tampoc - not either, neither

o - or

ni...ni - neither...nor

contudo - nevertheless

entons - then

así - so (conjunctive). therefore

en todo maneraz - in any case, regardless, anyway

de cualquel manera - anyhow (carelessly, haphazardly)

bastanch = quite, rather, sufficiently.

It takes the place of Spanish bastante.

realmén = really, truly, actually.

demasiadu = too much, excessively.

estremamén = extremely.

tan = so, to such a degree, to such an extent.

tan...com

as...as (when making a comparison)

tanto = so much, so many.

-íssime = really something. It is the same as Spanish -ísimo/a/os/as. This is an augmentative intensifier, also known as a superlative.

grevíssime = very serious, extremely grave.

povríssime = poorest.

Interrogatives (Question Words) and more

quíe - who [like French/Catalan 'qui', Latin 'qui', Spanish 'quién y quiénes', Italian 'chi']. One can make this

plural to say the equivalent of English "who all" - quíez

de quíe - whose (used in questions) [like Spanish 'de quién, de quiénes'].

cuye - whose (used in relative clauses), of which [like Spanish 'cuyo, cuya, cuyos, cuyas'; Portuguese 'cujo, cuja, cujos, cujas'].

quey - what (for questions) [like Spanish: qué]. One can make this plural to say the equivalent of English "what all" - queyez

que - that (conjunction), than [like Spanish que]

mais que - more than

menos que - less than

cual - which (of several) [like Portuguese, Spanish 'cual', and Italian 'quale'].

le que - that which (in relative clauses) [like Spanish: lo que; Portuguese: o que].

onde - where [like Portuguese and Galician 'onde', Catalan 'on', Romanian 'unde', and Spanish 'donde'].

a onde - to where?

d'onde - from where

cando - when [like Romanian 'când', French 'quand', Portuguese 'quando', and Spanish 'cuando'].

por quey - why, for what ['por que' is from Spanish 'por qué', Portuguese 'por quê', Italian 'perché', French 'pourquoi'].

Note the difference between Why and Because.

pasque - because [like Haitian Creole: paske; Spanish and Portuguese: porque, French parce que, Italian perché].

para que - in order that, so that

puis - for, on this account, because

como - how [like Catalan 'com', French 'comment', Spanish 'cómo', and Portuguese 'como']

cuanto - how much, how many [like Portuguese/Italian 'quanto', Spanish 'cuánto', and Catalan 'quant,quants'].

cuanto custo - how much, at what cost

Prepositions

Por versus Para?

Por can be used for many things as in Spanish and Portuguese. You use Para about the same as you do in Spanish. Per and Atravers, on the other hand, would likely be translated as Por in Spanish, because Voç Comune attempts to be less ambiguous.

para is used:

to indicate destination,

to show the use or purpose of a thing,

to mean "in order to" or "for the purpose of",

to indicate a recipient,

to express a deadline or specific time, and

to express a contrast from what is expected.

El saliú para Madrid. He left for Madrid.

Le tasa es para caví, le copa es para vino, i le vaso es para agua.

The cup (mug, has handle) is for coffee, the (wine) glass is for wine, and the glass (no handle) is for water.

Este vaso de tcha dolce es para vos. This glass of sweet tea is for you.

Le regaloz som para tu. The gifts are for you.

Jo necesitam esse camisa para sabado.

I need that shirt by Saturday.

Para un neño, el lesim machu bien.

For a child, he reads very well.

Jo treballam para ser rique. I work in order to be rich.

por is used:

to express gratitude or apology,

for velocity, frequency and proportion,

when talking about exchange, including sales,

to mean "on behalf of," or "in favor of,",

to express a length of time,

in cases of mistaken identity, or meaning "to be seen as",

to show the reason for an errand,

to express cause or reason, and

when followed by an infinitive, to express an action that remains to be completed, use por + infinitive.

Nus dam gratçaz por le comida. We gave thanks for the meal.

Nus vam ale restoranti cincu vecez por setmana. We go to the restaurant five times a week.

El la diú dieç dólêrez por le livro. He gave her ten dollars for the book.

Jo na votoú por el. I didn't vote for him.

vinte euroz por pesona 20 Euros per person

Ellez mi tenem por innobel. They take me for ignoble (not honorable in character or purpose).

per is from Catalan and Italian, and is used:

for means of communication or transportation,

in passive constructions, and

agent or cause of an object (written by, made by, designed by...)

Le livroz fui escrivide per Juan. The books were written by Juan.

El anni per bus. He went by bus...

A means to and is used in these ways:

to indicate motion —

Ilu caiú ale piso. It fell to the floor.

Nus vam ale ciudad. We are going to the city.

to introduce an indirect object —

Jo dam un camisa a Jon. I give (am giving) a shirt to Jon.

to connect a verb with a following infinitive — This use of A is especially common following verbs indicating the start of an action. In these cases, A is not translated separately from the infinitive. —

Ella comenciú a salir. She began to leave.

El entroú para favlar cun tig. He came in to talk to you.

Jo hau venidu a estudar. I have come to study.

Ella comenciú a bailar. She began to dance.

When referring to time — on time, at (time)

Nus solim ale cincu. We leave at 5.

Nus jegoú ale têmpo. We arrived on time.

Jo venim ale tres. I am coming at 3.

de lundey a sabado from Monday to Saturday/ Monday through Saturday

A is not used for means of travel as in Spanish; for that use per or via.

Nus viadjam per/via pied. We are traveling by foot.

acia means toward/towards and is similar to Spanish 'hacia':

{towards (not necessarily implying arrival), by (date in future)}

Nus caminam acia l'escola. We are walking toward the school.

atravérs is similar to French à travers and Portuguese através:

meaning "through," "along," "across", "by" or "in the area of". It is used to express an undetermined or general time, meaning "during". It can also mean from one side to the other (entering and exiting)

Le roqueto pasoú atravérs de l'edificio. The rocket went/passed through the building.

sobrê means on, about, concerning, and regarding, similar to Spanish and Portuguese 'sobre' and French 'sur':

Le livroz som sobrê filosofíê. The books are about philosophy.

Ilu es un programa sobrê le presidenti. It is a program on the president.

Voç Comune has two words that express 'in' and 'at': en and dêntro (de). They both express time and location. Please see the examples below.

En expresses the length of time an action takes (within or during the time span of). The verb is usually in the present or past.

Jo podem facer le cama en cincu minutoz. I can make the bed in 5 minutes.

El lesiú le livro en un uora. He read the book in an hour.

J’aprendeú a bailar en un añu. I learned how to dance in a year.

El jegará en iverno. He will arrive in winter.

Dante indicates the amount of time before which an action will occur. The verb is usually in the present or future tense.

Nus salim dêntro de dieç minutos. We’re leaving in 10 minutes.

El volverá dêntro de un uora. He’ll return in an hour.

Ella comencirá dêntro de un setmana. She will start in a week.

En is more general regarding the location. It can mean "in", "within an area of", and "at". It can also refer to "manner of being". Sometimes it corresponds to French à and en.

Ella estam en aula. She is in class.

El estam en Nuve York. He is in New York.

Jo habitam en Colombia. I live in Colombia.

Nus estam en paç. We are at peace.

Jo es bone en tocar le ghitara. I am good at playing the guitar.

El estam en le mesa. He is at the table.

dêntro de is used regarding the location when you want to express "inside". It also correlates to Spanish dentro.

El estam dêntro dele casa. He is in the house.

Le gato estam dêntro dele caija. The cat is in the box.

Le cachor estam dêntro dele jaula. The dog is inside of the cage.

Astê correlates with Spanish hasta and Portuguese até. It means a few different things, especially 'until, as far as, up to, and down to' (depending on the context).

Astê agora... Until now...(so far, up to now)

Astê (le) vindrey Until Friday

Jo dormim astê le seis. I am sleeping until 6.

Nus anni astê Managua. We went all the way to Managua.

astê certe puntu... up to a certain point...

Jo tenem cabello astê le cintura. I have hair down to my waist.

¿astê onde ...? how far...?

¿astê cando..? how long...for? (until, when)

astê nuve orden until further notice

astê entons until then

De corresponds to Spanish de meaning of or from and can indicate possession:

El es de Nuve York. He is from New York.

Jo preferam le carro de Juan. I prefer Juan's car.

Desde correlates to Spanish and Portuguese desde, meaning 'from or since'. It indicates motion stronger than just de.

L’avión viadjoú desde Peru astê Chile. The plane traveled from Peru to Chile.

El tiroú le beisbol desde le carro. He threw the baseball from the car.

Jo hau habitadu iquí desde que jo naiceú. I have lived here since I was born.

Jo na comeú desde ayeri. I haven't eaten since yesterday.

¿Desde cando tu sabem il? How long have you known it? (Since when...)

Desde que jo lu lesiú dêntro dele djornau, Since I read it in the newspaper,

Entre correlates to Spanish, Portuguese, and French entre, meaning 'among or between'.

Le cachor estam entre le mesa i le sofa. The dog is between the table and the sofa.

Nus tenem dos mill pesoz entre todo nos. We have 2 thousand pesos between all of us.

Tu elegirá entre esse tres livroz. You will choose between those three books.

Cun corresponds to Spanish con and Portuguese com meaning with:

Jo vam cun el. I am going with him.

Sens correlates to Spanish sin, Portuguese sem, Italian senza, French sans, and Occitan senz meaning without.

Nus vam sens el. We are going without him.

Jo na podem facer lu sens ver l’înstrucciónz. I can’t make it without seeing the instructions.

Le turistas jegoú ale hotel sens dinero. The tourists arrived to the hotel without money.

Contra corresponds to Spanish contra meaning against (not for):

Ella estava contra le welga. She was against the strike.

The prefix contra- means counter, against, opposing, contrary to

contrabando contraband

En frente de correlates to Spanish enfrente de meaning in front of:

Le gato estam en frente dele mesa. The cat is in front of the table.

Detrás de correlates to Spanish detrás de meaning behind:

Le cachor estam detrás dele mesa. The dog is behind the table.

Trás corresponds to Spanish trás meaning after, behind, and by:

Día trás día Day by day

Ellez estuvi caminandu uno trás outro. They were walking one after the other.

Encima de correlates to Spanish encima de and Portuguese em cima de meaning on top of:

Le gato estam encima dele casa. The cat is on top of the house.

Baiju and enbaiju de corresponds to Spanish bajo and debajo/abajo de meaning under:

Le cachor estam enbaiju dele mesa. The dog is under the table.

Fuera de correlates to Spanish fuera de meaning outside of:

Le cachor estam fuera dele casa. The dog is outside of the house.

Cerca de correlates to Spanish cerca de meaning near or around:

Le cachor estam cerca dele mesa. The dog is near the table.

Antes de correlates to Spanish antes de meaning before:

Jo lesiú antes de me dormir. I read before going to sleep. (putting myself to sleep)

Dopué de correlates to Portuguese depois de and Spanish después de meaning after:

Nus comem dopué de l'aula. We are eating after class. (We will eat after class)

Durant correlates to Spanish durante meaning during:

Nus dormiú durant le lición. We slept during the class.

Aun correlates with Spanish aun (not aún), and means even/including.

Aun le ricos sufrirá le crisi. Even the rich will suffer the crisis.

Aun asi, jo na podem facer il. Even so, I can’t do it. (Including those circumstances...)

Ainda correlates with Spanish todavía and aún, Portuguese ainda, meaning still/yet

Jo ainda na lu creím! I still don’t believe it!

Jo na hau vistu ainda le filmi. I still haven’t seen the film.

Jo querem facer ainda mais verde le gramado. I want to make the lawn even more green.

Según correlates to Spanish según meaning according to:

Según mev amigo ilu nevará. According to my friend it will snow.

Conciseness of words

Department, Secretary, Agency, Office, and Desk

Department, Secretary, Agency, Office, and Desk

A ministry or department of the government is a secretaría. It can also mean a secretaryship or a secretary's office.

The head of a ministry or department is a secretario, which is synonymous with secretary in the U.S. style of government and secretariat.

A biuro (bureau) is a subdivision of a larger agency usually within a secretaría (department of government) or large civic organization.

An agença is an agency that is usually independent but may be under a secretaría.

A consultorio is an office and place of consulting.

An oficina is a business office where an ofici (profession/trade/craft) is conducted.

An escritorio is a desk or place of writing.

An mostradora is a front desk or area for information.

A department of a supermarket or grocery store is a sección (section).

A departimento is a department of a university or large organization.

El estuvi siedide en su escritorio en le biuro. He was sitting at his desk at the bureau.

Le nuve supermercado tenem un sección floral. The new supermarket has a floral department.

El treballam dêntro dele Secretaría de Agricultura. He works in the Ministry/Department of Agriculture.

El estam en afeirs oficial para le secretario municipal. He is on official business for the town clerk.

Jo anni ale mostradora en le hotel. I went to the front desk in the hotel.

Mientras en l'universitá, ella favloú cun algom en le departimento de chiença informátic. While at the university, she talked with someone in the Computer Science department.

Go, Stroll, Walk, Drive, and Ride

The verb ir means to go. It is similar to Spanish and Portuguese "ir" and French "aller".

Jo vam ale tienda. I go to the store. I am going to the store.

El anni ale tienda ayeri. He went to the store yesterday.

Ellez irá ale tienda demañá. They will go to the store tomorrow.

The verb caminar means to walk. It is similar to Spanish, Portuguese, and Catalan: caminar/caminhar.

Jo caminam ale tienda. I walk to the store. I am walking to the store.

El caminoú ale tienda ayeri. He walked to the store yesterday.

Ellez caminará ale tienda demañá. They are walking to the store tomorrow.

The verb conducir means to drive a vehicle.

Jo conducim un carro. I drive a car.

Ella conducim un camión. She drives a truck.

El condujú un moto ale tienda ayeri. He drove a motorcycle to the store yesterday.

The verb montar means to ride a bike, horse, or other animal that is mounted.

Ella montam un bicicleta. She rides a bicycle.

Ellez montam cavaloz. They ride horses.

El montoú un elefanti anteyeri. He rode an elephant the day before yesterday.

Have, Hold, -tain

The verb tener means to have, hold, or keep. It is similar to English ending '-tain'.

When referring to age in Voç Comune, it is like Spanish and Portuguese:

Jo tenem trenta-iseis. I am 36 years old. (I have 36 years)

Ellez tenem un riunión ojui. They are having (holding) a meeting today.

By adding a prefix, we can come up with these verbs:

Sustener means to sustain, hold up, bear, and endure. Originally, it was from Latin (sub and tenere), [to hold from below].

Mantener means to maintain. Originally, it was from Latin (manu tenere), meaning [to hold in the hand].

Come, Become, Arrive, Leave, Return, and Revolve

The verb venir means to come.

The verb become is a little more complicated, but devenir can be used in most cases. In reference to gradual change, one can use jegar which means arrive at.

When arriving at a destination, also use jegar (Spanish: llegar, Portuguese: chegar).

The verb salir means to leave a location, and the verb rivolver means to come back (return).

Volver means to turn or change the orientation of.

Devolver means to return something.

The verb girar means to revolve or circle.

Ella viniú ale ciudad ace cincu díaz. She came to the city five days ago.

Jo deveniú enferme ayeri. I became sick yesterday.

Ellez jegoú a sus casa. They arrived to their home.

Jo salrá iquí demañá. I will leave here tomorrow.

El rivolveú ale tienda. He returned to the store.

Ella volvem le cabesa. She turns her head.

Nus devolveú livroz ale biblioteca. We returned books to the library.

Le Terra giram aredor dele Sol. The Earth revolves around the Sun.

To leave something behind is dechar (Spanish: dejar, Portuguese: deixar).

Nus dechoú le llaviz sobrê le mesa. We left the keys on the table.

Carry, Bring, Wear, Transport, Pull, and Ship

The verb trazer means to bring along.

The verb levar means to carry.

The verb llevar means to wear on the person, like clothes, a hat, and a watch.

Traher means to pull, draw, or plow and has a similar etymology as Spanish traer, Portuguese trazer, and English traction.

Egstraher means to extract and atraher means to attract.

To transport and to ship is transportar. Transportation is simply transporti.

Nus trazeú un caija de cervesa ale fiesta. We brought a case of beer to the party.

Jo levoú le bolsa de verduraz. I carried the bag of vegetables.

Le tractor traheú le terra para aerar le sulo por le coyeitas. The tractor plows the earth in order to aerate the soil for the crops.

Dos de tev dentiz devem ser egstrahide. Two of your teeth must be extracted.

Le sistema de transporti públic en le ciudad es machu eficiente. The public transportation system in the city is very efficient.

L'electrônz som atrahide per le protônz. Electrons are attracted by/to protons.

Eat, Dine, and Drink

The verb bever means to drink. Comer means to have a meal and manjer means to eat in general or to munch on.

Nus comem a medjedía. We eat at noon (midday). We are eating at noon.

Ella bevem caví cun letchi. She drinks coffee with milk.

Jo beveú un bevida gasiose cun mev comida. I drank a carbonated beverage (soda-pop) with my meal.

Jo manjem un bretzel. I eat a pretzel. I am eating a pretzel.

El manjeú un galeta ayeri. He ate a cookie yesterday.

Para l'amorso, nus comem pollo cun arris. For lunch, we are having chicken with rice.

Para le dena, ellez comem pañ de carni cun catchup. For dinner, they are having meatloaf with ketchup.

Para le dena demañá, nus comerá tacos de carni bovine. For dinner tomorrow, we will eat beef tacos.

Read, Write, Hear, and Listen

The verb lesir means to read and escriver means to write.

¿Gustam-tu de lesir? Do you like to read? | Do you enjoy reading?

Na, jo na gustam de lesir, peró jo gustam de escriver. No, I don't like to read, but I like writing.

Ella lli escriveú un carta. She wrote him a letter.

Quello estuvi un jole livro. That was a nice book.

Jo lesiú todo lu en dos díaz. I read all of it in two days.

Le charta fui escrite ace dos-cento añuz. The charter was written 200 years ago.

The verb ovir means to hear and escutchar means to listen. There is a difference, but sometimes one can be used in place of the other.

Jo te ovim claremén. I hear you clearly.

El escutcham a su aviso. He listens to her advice.

Jo escutcham ale radio. I listen to the radio.

Nus oviú un ruido. We heard a loud sound.

See, Watch, Observe, Show, Demonstrate, and Prove

The verb ver means to see or view, mirar means to watch, and observar means to watch attentively or observe.

To watch with care and be mindful of is cuidar.

Le neñoz miram le televizión. The kids watch the television. The children watch t.v.

Mev padrê cuidam mev fillo. My dad watches my son.

Ellez observoú l'egsperimento interesante. They observed the interesting experiment.

Jo vem un páxaro en l'árbor. I see a bird in the tree.

The verb mostrar means to show and the verb demostrar means to demonstrate or prove.

Feel, Sense, and Smell

The verb sentir is to feel or sense.

¿Sentim-tu le vanto? Do you feel the wind?

The verb oler means to smell or sense the aroma of.

J'olem un ghisado picose. I smell a spicy stew.

More Descriptive Words for Love

The Greeks used four terms for love. Voç Comune language uses these terms as well to describe varying types of love.